Black Wall Street

What was Black Wall Street?

Black Wall Street was an African American business district in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the early 20th century. People called the area Black Wall Street because of its economic prosperity.

Black Wall Street became an enclave for Black entrepreneurs and a gateway for economic prosperity. As a self-sustaining district, it became a beacon of wealth for business owners, while establishing independent school systems and public services. At the time, several millionaires emerged out of the thriving metropolis.

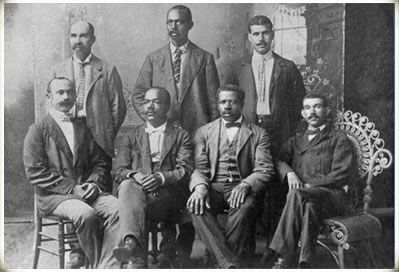

Business Owners of Black Wall Street

Ottawa W. Gurley (aka O.W.) was a turn-of-the-20th-century Black educator, entrepreneur, and landowner who was born to former enslaved Africans. In 1889, after resigning from a position he held with the Grover Cleveland presidential administration, O.W. moved from his home state of Arkansas to Perry, Okla., in order to participate in the Oklahoma Land Grab of 1889. With his wife Emma, he later relocated to Tulsa to seize economic opportunities resulting from the city's multiracial population boom. Once there, O.W. purchased a 40-acre tract of undeveloped land, where he built a grocery store on a dirt road that ran just north of the train tracks traversing the city.

O.W. later forged a partnership with fellow Black businessman John the Baptist Stradford (aka J.B.), with whom he shared a general distrust of White people. Both men chose to go by their initials instead of their first names. This action was a form of silent protest because men in the South were customarily addressed by their surnames, while boys were called by their first names. Sadly, White men often addressed Black men by their first names as a form of emasculation. By using their initials, O.W. and J.B. circumvented this practice.

O.W. and J.B. occasionally held divergent opinions. For example, while O.W. subscribed to the philosophies of African American educator Booker T. Washington, J.B. favored the more radical views of civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois. Despite their differences, the pair worked in lockstep to develop an all-Black district in Tulsa. They subdivided the land into housing zones, retail lots, alleys, and streets, all of which were exclusively available to other African Americans who were fleeing lynchings and other racial horrors.The

The Origin of Greenwood

After O.W. built several square two-story brick boardinghouses near his grocery store, he called the street on which these structures sat Greenwood Avenue, after the Mississippi town from which many of his early residents hailed. Before long, the entire area became known as Greenwood, which soon became the site for a school, as well as an African Methodist Episcopal Church. But O.W.’s crowning project was the Gurley Hotel, whose high quality rivaled that of the finest White hotels in the state.

What Was Black Wall Street Famous For?

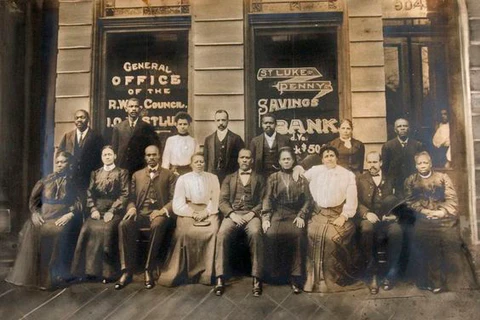

Black Wall Street, located in the Greenwood neighbourhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma was one of America's most prosperous business districts in the early 20th century. The district became an economic powerhouse, with independent schools, banks, hotels, and transit systems.

Business of Black Wall Street

In 1921, the Greenwood section of Tulsa contained 108 Black-owned businesses, including 41 grocery and meat markets, 30 restaurants, 11 boarding and rooming houses, nine billiard halls and five hotels. Greenwood also had 33 Black professionals, including 15 physicians and surgeons; six real estate, loan and insurance agents; four pharmacists; three lawyers; and two dentists. Twenty-four skilled crafts persons in the community included 10 tailors, five building contractors and painters, and four shoemakers. The community’s 26 service workers included 12 barbers, six shoe shiners and five clothes cleaning shops.

The 600+ businesses of Black Wall Street included 30 grocery stores, 21 churches, 21 restaurants, two movie theaters, schools, libraries, law offices, a hospital, a bank, a post office, and a bus system. Community members also owned six private airplanes.

https://www.history.com/news/tulsa-massacre-black-wall-street-before-and-after-photos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre

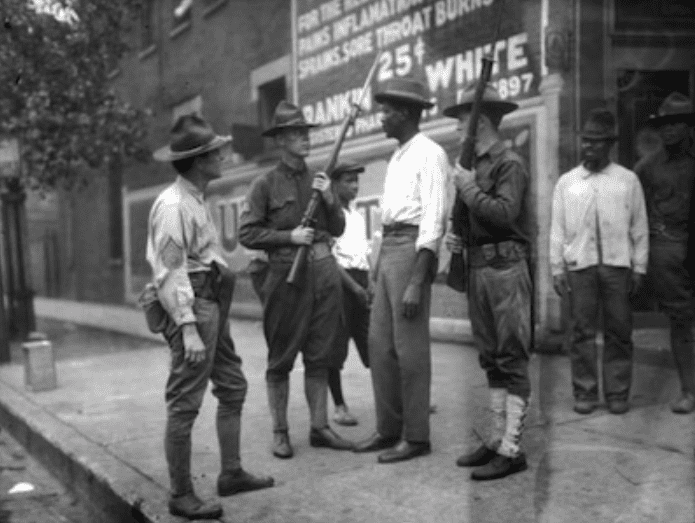

The Tulsa race massacre, also known as the Tulsa race riot or the Black Wall Street massacre,[12] was a two-day-long white supremacist terrorist[13][14] massacre[15] that took place between May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, some of whom had been appointed as deputies and armed by city government officials,[16] attacked black residents and destroyed homes and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The event is considered one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history.[17][18] The attackers burned and destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the neighborhood—at the time one of the wealthiest black communities in the United States, colloquially known as "Black Wall Street".[19]

More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals, and as many as 6,000 black residents of Tulsa were interned in large facilities, many of them for several days.[20][21] The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead.[22] The 2001 Tulsa Reparations Coalition examination of events identified 39 dead, 26 black and 13 white, based on contemporary autopsy reports, death certificates, and other records.[23] The commission gave several estimates ranging from 75 to 300 dead.[24][12]

The massacre began during Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, a white 21-year-old elevator operator in the nearby Drexel Building.[25] He was arrested and rumors that he was to be lynched were spread throughout the city, where a white man named Roy Belton had been lynched the previous year. Upon hearing reports that a mob of hundreds of white men had gathered around the jail where Rowland was being held, a group of 75 black men, some armed, arrived at the jail to protect Rowland. The sheriff persuaded the group to leave the jail, assuring them that he had the situation under control.

The most widely reported and corroborated inciting incident occurred as the group of black men left, when an elderly white man approached O. B. Mann, a black man, and demanded that he hand over his pistol. Mann refused, and the old man attempted to disarm him. A gunshot went off, and then, according to the sheriff's reports, "all hell broke loose".[26] The two groups shot at each other until midnight when the group of black men were greatly outnumbered and forced to retreat to Greenwood. At the end of the exchange of gunfire, 12 people were dead, 10 white and 2 black.[12] Alternatively, another eyewitness account was that the shooting began "down the street from the Courthouse" when black business owners came to the defense of a lone black man being attacked by a group of around six white men.[27] It is possible that the eyewitness did not recognize the fact that this incident was occurring as a part of a rolling gunfight that was already underway. As news of the violence spread throughout the city, mob violence exploded.[2] White rioters invaded Greenwood that night and the next morning, killing men and burning and looting stores and homes. Around noon on June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law, ending the massacre.

About 10,000 black people were left homeless, and the cost of the property damage amounted to more than $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property (equivalent to $38.43 million in 2023). By the end of 1922, most of the residents' homes had been rebuilt, but the city and real estate companies refused to compensate them.[28] Many survivors left Tulsa, while residents who chose to stay in the city, regardless of race, largely kept silent about the terror, violence, and resulting losses for decades. The massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories for years.

Click on the pdf below to read a record of Black Wall Street's destruction and how it came about.

The Destruction of Black Wall Street Tulsa.pdf